Biography

I am a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Accountancy, Economics and Finance at Hong Kong Baptist University. My research focuses on Computational Social Science, Labor Economics, and Education Economics, with a particular emphasis on China. Previously, I was a Postdoctoral Scholar at the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions (SCCEI).

I hold a Ph.D. in Political Science with a specialization in Computational Social Science from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), obtained in 2023. I also earned an MPhil in Social Science from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) in 2016 and an MA in Finance from Xiamen University (XMU) in 2014.

In addition to my current role, I am a faculty affiliate to the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions (SCCEI) and UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation (IGCC).

Download my resumé.

- Computational Social Science

- Labor Economics

- Education Economics

-

Ph.D. in Political Science (with a Specialization in Computational Social Science), 2023

University of California San Diego

-

M.Phil in Social Science, 2016

Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

-

Master in Finance, 2014

Xiamen University

-

BSc in International Business and Trade, 2010

Xiamen University, Tan Kah Kee College

Research

Peer-Reviewed Articles and Working Papers

This study examines whether and how industrial robot adoption affects corporate pollution emissions. Using a sample of 163,301 firm-year observations from the Chinese industrial enterprises for the period 2004–2014, we find that firm’s robot adoption is positively related to pollution emissions reduction. Further mechanism tests show that the adoption of robots in production can improve a firm’s productivity and alleviate a firm’s financial constraint, thereby increasing the firm’s pollution emissions reduction. In addition, we find that the above-mentioned effect of robot adoption on a firm’s pollution emissions reduction is more pronounced for firms headquartered in regions with strong environmental regulations, firms that are high efficiency of pollution treatment and high technology-intensive, firms that have gone public and state-owned enterprises. Altogether, this study provides the first micro evidence on the relationship between robot adoption and corporate pollution emissions, providing significant implications for the world’s sustainable development.

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) has led to its widespread application across various domains, including financial technology (FinTech). However, public skepticism persists due to concerns over the unpredictability and biases of AI-powered systems. Through experiments involving two LLMs (GPT-4 and Claude 3 Opus) and 1,095 human participants across 12 task sets, we investigated biases in large language models (LLMs) when making default judgments in peer-to-peer lending within the FinTech sector and examine decision-making performance and trust dynamics in human-machine collaboration. Our results indicate that LLMs consistently outperform humans in judgment accuracy—even without prior training on Chinese-language data and when processing unstructured information—highlighting their potential efficacy in FinTech applications. Both LLMs and human participants exhibit different bias structure, a mixing of elements of taste-based and statistical discrimination. Notably, LLMs exhibit a stronger tendency to lower the threshold for loan approvals for women, while imposing stricter loan terms on them, such as reduced lending amounts and higher interest rates. In collaborative settings, inputs from GPT-4 enhance human judgment accuracy, but providing human input does not improve the performance of either humans or LLMs. Participants exhibit significant algorithm aversion, which diminishes as the complexity or stakes of the lending situation increase. Additionally, women show a more pronounced algorithm aversion than men, although this difference lessens with higher complexity or lending stakes. These findings underscore the nuanced interplay between AI and human decision-making in FinTech lending and beyond, emphasizing the need for careful integration of AI systems to mitigate biases and improve lending outcomes.

Shadow education in China is a significant social issue and a leading factor in exacerbating education inequality that fosters over-competition. In July 2021, the Chinese government implemented the Double Reduction Policy, which banned for-profit academic private tutoring. We estimate the economic consequences of this policy on the education industry in China by employing two novel datasets containing online job postings and firm registration information. We find that within four months after the policy implementation, online job postings for tutoring-related firms decreased by 89%, tutoring-related firm entry decreased by 50%, and their exits tripled. Cities with 10,000 (2%) more children lost 50 (3.7%) more education-related job opportunities, experienced 0.3 (5.9%) fewer firm entries, and 0.1 (1.3%) more firm exits per month. Surprisingly, not only academic tutoring firms were impacted, but also untargeted businesses involving in arts and sports tutoring were also heavily struck, although they were encouraged by the policy to promote children’s non-academic ability. This negative spillover can be partly explained by the interconnected ownership structure among academic and non-academic tutoring firms. Back-of-the-envelope calculations show that this policy led to 3 million job losses in four months and at least 11 billion RMB Value Added Tax losses in 18 months nationally.

Can tougher laws effectively deter criminal activities? Legislative efforts aimed at combating crime often result in the unintended displacement of criminal activities. Leveraging a prostitution-related judicial interpretation in 2017, which specified the minimum number required to qualify as organized pimping to three, we evaluate the Chinese government’s recent legal efforts to combat organized prostitution. While the judicial interpretation aimed at reducing prostitution activities through the crackdown on pimps, we find that the judicial interpretation is more effective at facilitating prosecutions against pimps operating in previously conspicuous establishments.

In this paper, I explore the unexpected consequences of Weibo’s geographic tagging policy in China, a case study that offers broader insights into information control in authoritarian regimes. Intended to “Build a National Wall” against overseas influence, this policy inadvertently created “Provincial Walls” within the country. Using unique high-frequency panel data from 200 influential Weibo accounts and a data leakage incident, coupled with a rigorous methodological approach, I demonstrate that the policy effectively reduces public discourse and regime-threatening information. However, it does so not by suppressing overseas users but by deterring domestic users from engaging in out-of-province discussions. This policy also has unintended effects, such as strengthening local identities, which can intensify geo-group division at the expense of national cohesion, and heighten cross-provincial conflict, potentially exacerbating social tensions. These findings reveal the complex impacts of user tagging policies in authoritarian regimes. While they may offer short-term benefits in controlling information, they can also create long-term challenges by aggravating the dictator’s informational dilemma and fostering conditions conducive to collective action.

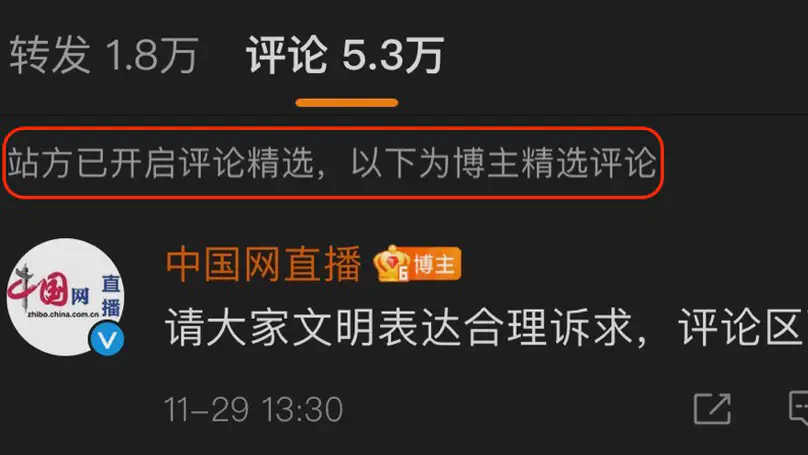

In this study, we examine the moderation of comment sections by government-affiliated accounts on Sina Weibo, a popular social media platform in China. While previous research has examined the separate strategies of censorship and propaganda used by authoritarian regimes to control information, our work aims to bridge the gap by examining the intersection of these two tactics in China. Specifically, we focus on how government-affiliated accounts use propaganda content and censor undesirable comments under their posts. We utilize a unique, high-frequency dataset and conduct two survey experiments to answer three research questions. First, why and when government-affiliated accounts choose to moderate their comment sections? Second, what are the causal effects of comment section censorship on remaining content and user engagement. Third, how does comment section moderation influence public opinion by altering second-order beliefs.

Employing news reports that appeared in Chinese national and local newspapers (2000 - 2014) coupled with data on the networks of elites, we find that local bureaucrats connected to strong national leaders tend to criticize members of weaker factions in politically damaging news reports. These adverse reports indeed harm the promotion prospects of the province leaders reported on in the articles, weakening the already weak factions and expanding the relative power of the strong factions.

Using a panel on the political turnovers of 1,201 prefecture leaders in China during 2002-2012, I find that, of all 1,816 serious coal mine accidents, even controlling for the number of deaths they caused, only those with exceptionally higher media coverage have the effect of significantly reducing the prospects of local leaders' promotion.

Data Insights

Exploring Politics, Economics, and Society through Data-Driven Insights

Contact

- leoyang@hkbu.edu.hk

- +1 (858) 405-2327

- Room 533, Wing Lung Bank Building for Business Studies (WLB), HKBU, Kowloon Tong,